Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL)

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is located toward the front of the knee. It is the most common ligament to be injured. The ACL is often stretched and/or torn during a sudden twisting motion (when the feet stay planted one way, but the knees turn the other way). Skiing, basketball, and football are sports that have a higher risk of ACL injuries.

Types of ACL Injuries

ACL injuries are diagnosed through clinical examination and MRI, and can be classified by the amount of damage to the ligament (partial or complete disruption). Injury to the ACL is usually a complete disruption, classifying it as a Grade III complete tear.

Grade I Sprain - There is some stretching and micro-tearing of the ligament, but the ligament is intact and the joint remains stable. These injuries rarely require surgery.

Grade II Sprain (Partial Disruption) - There is some tearing and separation of the ligament fibers and the ligament is partially disrupted. The joint is moderately unstable. Depending on the activity level of the patient and the degree of instability, these tears may or may not require surgery.

Grade III Sprain (Complete Disruption) - There is total rupture of the ligament fibers. The ligament is completely disrupted and the joint is unstable. Surgery is usually recommended in young or athletic people who engage in sports that involve cutting or pivoting.

causes

The anterior cruciate ligament can be injured in several ways:

Changing direction rapidly

Direct contact or collision, such as a football tackle

Stopping suddenly

Slowing down while running

Landing from a jump incorrectly

Several studies have shown that female athletes have a higher incidence of ACL injury than male athletes in certain sports. It has been proposed that this is due to differences in physical conditioning, muscular strength, and neuromuscular control. Other suggested causes include differences in pelvis and lower extremity (leg) alignment, increased looseness in ligaments, and the effects of estrogen on ligament properties.

Symptoms

Most patients will report a "popping" noise and describe their knee “giving out” from underneath them. Other common symptoms can include:

Pain with swelling. Within the first 24 hours, patients will most commonly experience knee swelling. Although the pain and swelling can go down with time, an ACL injury is likely to have occurred if the patient does not have stability in the knee when attempting to make any fast cutting or twisting movements.

Loss of full range of motion

Tenderness along the joint line

Discomfort while walking

Treatment Options

Nonsurgical Treatment

A torn ACL will not heal without surgery. Despite this, some patients may chose nonsurgical treatment if they are elderly or have a very low activity level. In these instances, the following treatment options may be available:

Your Sports Medicine doctor may recommend a brace to protect your knee from instability. To further protect your knee, you may be given crutches to keep you from putting weight on your leg.

Physical therapy and rehabilitation could also be beneficial for patients who elect non-surgical treatment. Your Physical Therapist will provide various exercises to restore function to your knee and strengthen the leg muscles that support it.

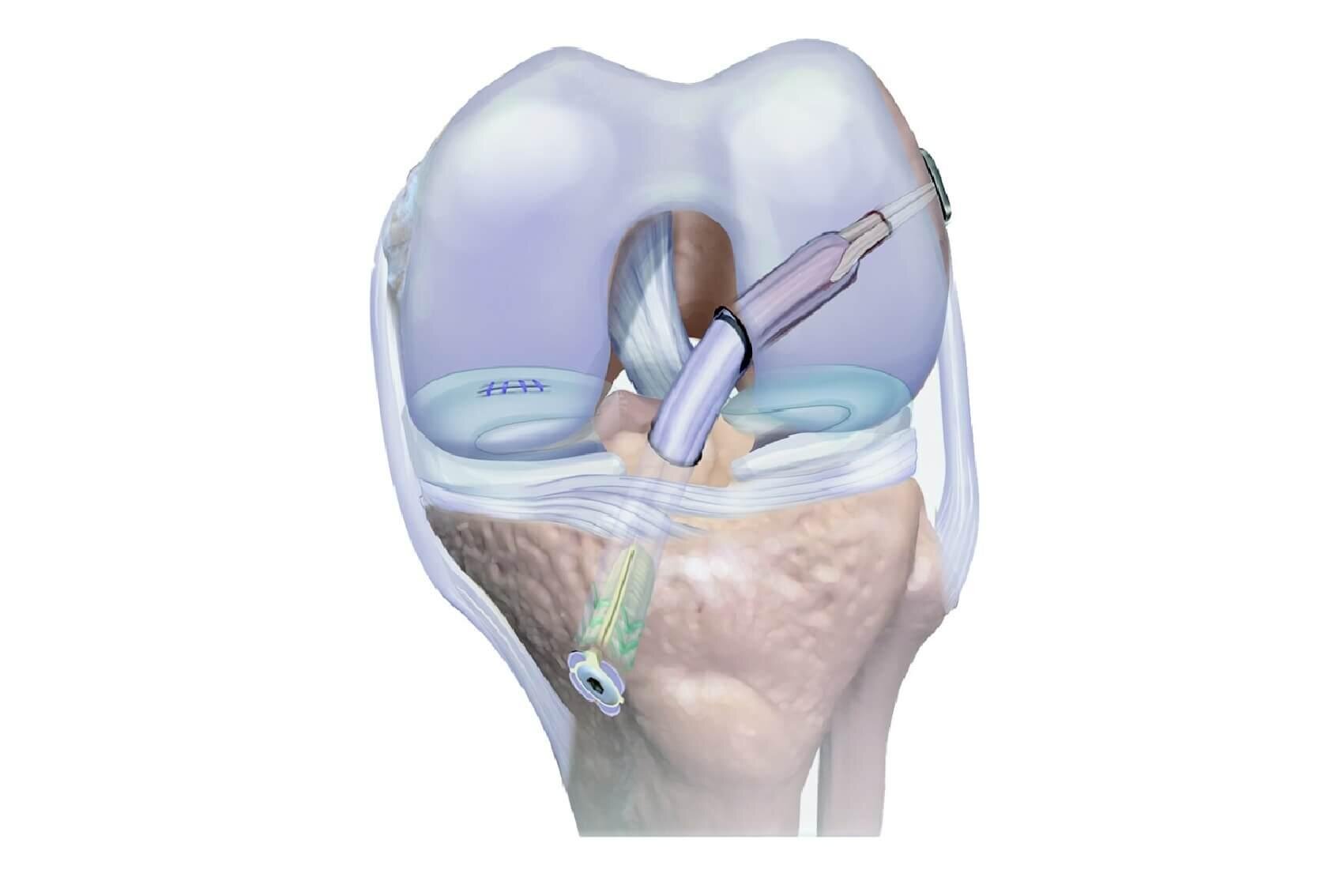

ACL Repair is seen in Image A and ACL Reconstruction is seen in Image B

Surgical Treatment: REPAIR VERSUS RECONSTRUCTION

A surgical repair of the ACL refers to affixing the injured ligament back to the tibia or femur from which it has been torn. In rare cases, the ligament may have pulled off of the bone and may have taken a small piece of bone with it. In such cases, the surgeon can suture the ligament or screw the bone back down and restore some, if not all, of the ACL's function.

However, a torn ACL is rarely able to be repaired because during most tears, the ligament tears at its midpoint, like a frayed rope. Over time, the ligament may become completely disabled. Even if partially intact, a torn ACL sustains tissue damage and repair of the original ligament has shown to provide relatively poor functional results.

Reconstruction of the ACL involves rebuilding it using a new ligament. The surgeon creates a soft tissue substitute for the ligament, called a graft, that re-establishes knee stability and provides a scaffold. The patient’s body will recognize this graft scaffold, populate it with living cells and permanently attach it in place. Over a relatively short time (about four to six months), this new ligament will take on the appearance and function of the normal ACL. The functional results of ACL reconstruction are predictably excellent and the overwhelming majority of patients are able to get back to the same or higher degree of athletic activity without pain or instability.

Grafts can be obtained from several sources. Often they are taken from the patellar tendon, which runs between the kneecap and the shinbone. Hamstring tendons at the back of the thigh are a common source of grafts. Sometimes a quadriceps tendon, which runs from the kneecap into the thigh, is used. Finally, cadaver graft (allograft) can be used.

There are advantages and disadvantages to all graft sources. You should discuss graft choices with your own orthopedic surgeon to help determine which is best for you. Because the regrowth takes time, it may be six months or more before an athlete can return to sports after surgery.

Find our ACL Surgery Post-Operative Instructions HERE.

Our Sports Orthopedic Team

J. Steve Smith, MD

Director of Orthopedics

Curriculum Vitae

Timothy Wilson, MD

Sports Orthopedic Surgery

Curriculum Vitae

Sambhu Choudhury, MD

Pediatric & Sports Ortho

Curriculum Vitae